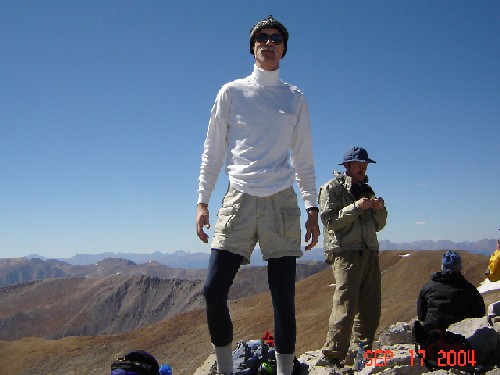

"Goat Mountain" (8,510 ft.)

With the Eta Aquarid meteor shower set to peak on Monday morning (the 5th), I knew I could spot a few of these meteors a day earlier (since the Eta Aquarids have a relatively broad peak), and the weekend was going to work a lot better for me. So I hit the road at just before

I was hiking by headlamp by

Despite my best efforts at an early start, the first tinges of dawn were already washing the sky, so I knew I wouldn’t have long. But I found a gently slanted rock on which to recline, and, using my pack as a pillow, I donned my one extra layer of insulation, extinguished the headlamp, and stretched out to soak up the celestial show. The temperature was probably still only in the thirties, but with virtually no wind, I was perfectly comfortable.

After about ten minutes, however, I realized that I probably wouldn’t see much more than the two meteors which had appeared. Since my goal was to get back home before

This is the second time since last summer that I have ended up hiking down to my target peak. Not only is Goat Mtn. 800 feet lower than

As I headed down the east side, I also discovered the trail—which I had totally missed back in December—which leads right to the summit. I followed it down until it turned north (not very far!), and then set off on my long bushwhack for the day: following the ridge crest over (and down) to

This section provided the most excitement, and the most uncertainty, of the day. Looking at the map, I estimated that the distance from Gray Back to Goat was going to be nearly the same as the distance from the trailhead to Gray Back. What I could not tell from a map with 100-foot contour intervals was just how rough the ridge in between was going to be.

What I found was a long series of ridge points, most of which were gently sloped on the west side, and much steeper and rockier on the east side. I eventually lost count of just how many there are, but I think it’s seven or eight at a minimum. Now, some of them are quite small, but a couple involve elevation gains (on the way “down”) on the order of 400 or 500 feet. And my out-and-back route required me to do them all in both directions.

I quickly found that the rocky sections tend to be quite pointy, so that strict staying on the ridge crest is often difficult. The north sides tend to be a little easier to negotiate, and I repeatedly dropped slightly off the crest on that side. As this terrain is all below timberline, however, both the rocks and the forested areas below them are frequently choked with some mixture of growing trees, downed trees, bushes and/or scrub oak. This made for truly difficult going in places although, thankfully, it never lasted very long.

When I topped out on the last major ridge point before reaching my destination, I took a look at the drop-off on the other side, and decided that here I had better make a major deviation from my original route plan. I simply couldn’t see the route down to the next saddle. So, to avoid dangerous cliffing-out, I opted to take a much more circuitous route, dropping seriously off the north side in an effort to stay below the rocks. This got me onto very steep slopes choked with a lot of timber and brush. It also didn’t entirely spare me from having to descend some interesting little patches of steep rock. Thus, getting to that next saddle ended up taking me nearly 20 minutes from the top. Here I finally began to wonder if I actually would have enough time to complete this adventure as planned!

Fortunately, that was the only difficulty of that magnitude, although one significant ridge point did remain before I could finally finish giving up elevation and start the actual climb of

Finally, nearly three hours out from the trailhead, I was presented with the final challenges: Which of the three closed contours shown on the Pikes Peak Atlas at 8,500 ft. was the true summit? And, was there the magic 300 feet of rise from the saddle to qualify this out-of-the-way peak as ranked, instead of its literature status as soft ranked?

(A note of clarification here for anyone not familiar with the nomenclature: When a peak hasn’t been benchmarked, and many haven’t, all you have to go on for determining its exact elevation is the relevant contour map. The peak’s elevation, as well as that of the relevant saddle, thus both have a range of possible values. For a topo map with 40-foot contour intervals, a range of almost eighty feet is therefore possible for the difference. This is the “rise” which determines whether or not a peak is given a ranking number by elevation within the state.)

I measured the saddle’s elevation as 8,212 ft., the north summit rock as 8,542, the middle summit as 8,532, and the south summit as 8,530. That makes the north peak the true summit, with a rise of 330 feet: enough to qualify! Since 8,542, however, is actually over what the next contour line would show, I have to question the accuracy of my GPS unit, which I’m accustomed to seeing read a bit high. The difference should still be solid, making Goat Mountain suitable for wedging in as the “3297-and-a halfth” highest peak in Colorado.

It was, as I had hoped, a gloriously sunny morning, with scarcely any wind. By the time I headed back down to being the return climb to Gray Back, it was just before

I was going to be satisfied with making the return journey in no more time than the outgoing leg, considering that I had had to give up some 1,100 feet to reach the last saddle. And that was the net figure, without even figuring in and up-and-down over all the ridge points in between. When I came to the large ridge point where I had taken such a time-consuming detour outbound, I studied its east side carefully from the better vantage point of the next point east.

What I saw convinced me that a direct assault on the rocks of the east face, although steep, was perfectly doable. I also concluded that it would actually take less time than any detour I could arrange, since it would almost totally eliminate the need to deal with timber and thick brush. This turned out to be correct: The scramble up the rocks definitely qualified as Class 3, but good gullies and ledges led all the way up, and it took scarcely ten minutes to make the climb. It was the most technically difficult climbing, and the most thoroughly enjoyable, that I did all day, with the warming sun at my back.

Shedding clothing all the way, I made it back to the summit of Gray Back at exactly

I have only coarse estimates for my distance and vertical on this trip. I had forgotten to charge batteries for my GPS, so I didn’t try to keep it running. I merely turned it on at points where I wanted to check location or altitude, so it gave me no distance figure. I also gave up any serious attempt to add up all the little increments of climbing and descending on that ridge. Judging from the map, and gross elevation stats, I estimate something like eight miles RT and 2,200 feet (at least!) vertical. Especially with the excellent weather, this was a really enjoyable excursion for an obscure peak.

Pictures are at:

http://picasaweb.google.com/tcogwr/GoatMountain

Long life and many peaks!