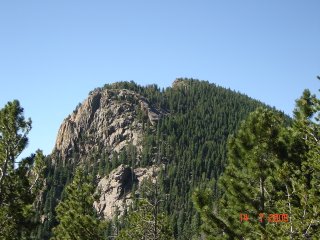

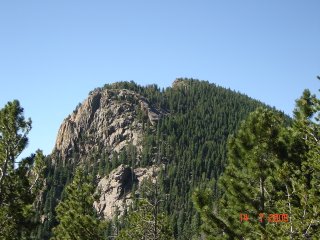

Stove Mountain

23 October, 2006: I’ve taken the trail that goes up past St. Marys Falls more than a dozen times, en route to Mt. Rosa to the west. Each time, the trail has brought me to within a half mile or so (as the crow flies) of the summit of Stove Mountain. You get a good view of the cliff face on the east side of Stove from the trail, and I’ve always told myself that, one of these times, I would either make it a destination in and of itself, or make a slight detour on one of my Rosa climbs, and finally bag this summit.

I knew it wasn’t likely to be a difficult summit, despite the impressive look of the east face. The western side is a gentle, forested slope leading to the abrupt drop-off at the top. It’s not even very high: The topo figure is 9,781 ft. Given that virtually all Colorado mountains have “gained” 5 to 8 feet as a result of satellite re-measurements, I figure 9,785 is probably a fairly accurate figure—well below timberline. Still, it’s a named summit, and I had never climbed it.

So, since Suzi’s return from her art trip to New York had made it unfeasible for me to do my usual Sunday run, and, better still, since the forecast for Monday was for sunshine all day long, I decided that the time had come to give Stove Mountain a try at last. I left the Gold Camp Road parking lot trailhead at exactly 10 am MDT.

I wasn’t sure how long this run/climb would take me, because there’s some bushwhacking involves once one leaves the trail, just above the falls. I had actually found a couple of trip reports online which mentioned indistinct sections of trail, and the topo map actually shows a trail part of the way up the west side of the mountain. But my sense was that quite a lot of the route would involve dead-reckoning plowing through the trees. I was right.

Just under an hour and a half sufficed to get me above the fall, to where I had noticed a trail spur leading south, down into the creek drainage which feeds St. Marys Falls. The drop of just a few dozen feet to the creek revealed no sign of a trail any farther. This may have been because, in late October, the north-facing slope on the other side (and in the bottom) was already covered with a few inches of snow. Thus, I simply started slogging through the snow, heading up and generally south-southeast, aiming for the saddle I had seen from the trail, west of my target summit.

The snow was not deep. Thankfully. I might have been a bit more comfortable if I had been diligent to bring gaiters—my socks did eventually get soaked—and it would have been truly uncomfortable if the temperature had been low enough. But it was a sunny, warm day, and not a cold, windy one, so I was okay. Besides, I was trying to travel light, carrying only a small belt pack, so I didn’t really have room to carry gaiters anyway. I had worn two long-sleeved shirts, plus a windbreaker, at the trailhead, and I fully expected to shed some layers along the way.

Slogging through the snow, and navigating essentially blind through the trees, I found that I was approaching a rounded summit which I hoped was just west of my objective. When I came around its north flank to the east side, however, I could finally see that I was still north of the saddle I wanted to hit. Also, I had lost a bit of elevation after skirting the little summit, and had to re-climb it on an ascending traverse to the south to get back on course.

All of this really only took a few minutes, however; the distances involved are not really very great. It’s just that you can’t see much most of the time. Once, this would have intimidated or scared me. With years of experience plowing around the high country, however, I knew I would make it to where I wanted to be, even if the route turned out to be somewhat circuitous.

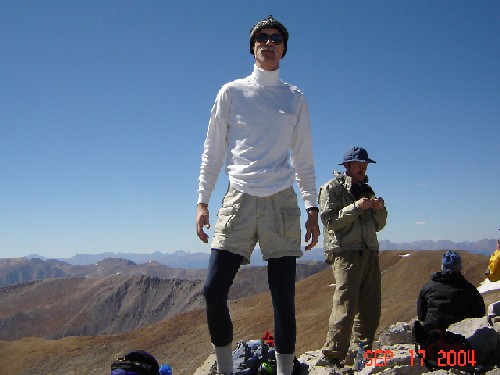

About an hour and forty-five minutes into my climb, I hit the saddle just west of the summit. I stopped to take some pictures, showing the rest of the route, as well as the view of higher peaks to the west and northwest. At this point, too, I basically lost the snow cover, thanks to the more southward-facing aspect of the terrain, and the reduced number of trees. From that point on (only about 350 vertical feet), there were only patches of snow, and it was mostly scrambling on warm, bare rocks.

Depending on your taste, this last leg of the climb could be anything from an easy walk-up (albeit through fairly dense timber) to at least a Class 4 scramble. I chose a middle line, between the forested slopes on the left (north) and the rocky cliffs on the right (south). Some low-level scrambling just off the edge of the cliffs kept me mostly out of the trees—and the snow—but made for easier going than the serious climbing of the rocks. Fifteen minutes from the saddle brought me out onto the relatively flat area of the false summit, just southwest of the true summit. Naturally, the view opened up dramatically at this point, especially to the north and east.

The true summit is actually more hidden in trees than this false summit, and only a few feet higher. So, I took a picture looking across the flat area, which is totally bare of vegetation, toward the summit. Then I traipsed across to the actual high point, where I got the pleasant surprise of the day.

Tucked into the cleft of the rocks forming the actual highest point of this mountain, there is actually a register! When I opened the salad dressing jar in which it was contained, I found that it was made from a small spiral notebook, and the inside cover revealed that it had been placed there in December of 2002 by none other than Mike Garrat, co-author of “Colorado’s High Thirteeners.” In four years, the jar had remained intact, the register dry and in good condition. There were perhaps 30 entries, total; I happily added my own.

I marked the summit on my GPS, which recorded an elevation of 9,810 ft. Then I took a couple of additional pictures, including one of the summit of Pikes Peak, just visible over the intervening hills.

I spent about 15 minutes on the summit, then headed down. I was hoping to make it back to the trailhead in about an hour and a half. Before leaving the summit area, however, I took one picture looking basically straight down, over the cliff edge on the southeast side, to show just how steep this side of the summit block really is. A careful inspection of what I could see from the trail on the way down convinced that there might be one or more free-climbable lines up the east or southeast side, however, and I certainly intend to return one of these days to explore that possibility. It would be a real rush to gain this summit via a scramble up that impressive east face!

In less than an hour from the summit, I was back below St. Marys Falls, making good time. Then, however, the snow and ice on the shaded trail finally got the better of me, and I sustained what I have to chalk up as my first actual injury while climbing in the mountains. I slipped on a steep section of trail and managed to twist my right ankle in the gyrations needed to bring myself to a stop. I was forced to do an asymmetric limp back to the trailhead, taking much longer than planned. Indeed, as I write this, my elastic-wrapped ankle is still giving me occasional twinges, and it will be a few days before I can run again. Thus, my time down is sort of meaningless. Oh, well: I should have been more careful, and I certainly will in the future. And not to worry: it is healing.

Pictures from the trip can be seen at:

http://new.photos.yahoo.com/cftbq/album/5764607623307899681#page1

and

http://www.imagestation.com/album/pictures.html?id=2100339006

As always, long life and many peaks.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home